For many years I tried to be the perfect expert in the field of Enterprise Architecture. I would read everything I could get my hands on, study cases, examples and anecdotes; talk to hundreds of people, and keep comparing notes with other ‘experts’ to find the answers to my employers’ and clients’ pressing questions. At some point, I even joined an international advisory organisation to figure out what the secret was of the ‘professional experts’ they so successfully sold to their international clientele.

I both failed and succeeded!

I succeeded in getting seen as an expert by clients and peers. Peers would happily engage with me in deeply intellectual discussions about frameworks, methodologies, ontologies and definitions. Clients would regularly reach out to me to tap into my ‘wisdom’ (such as it might be) and get the ‘right’ answer to problems they were struggling with.

Source: Grove City College (2015)

Where I failed was first of all in convincing myself that I actually was the expert others wanted to see in me. The old cliché that the more you know, the more you know you don’t know was certainly true for me. No matter how much I read, studied and analysed, I increasingly felt I had more questions than answers. As the sphere of my understanding grew, the surrounding sphere of mystery, unknowns and unknowables expanded even more. The more I knew, the less wise I knew myself to be.

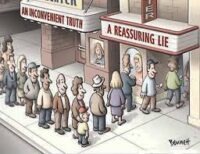

However, the failure that struck me most was that even when I felt I was providing reasonably useful answers and pointing clients and peers in directions I knew to be viable and sound, I noticed that those answers had minimal impact on the recipients’ understanding and future actions. It was as if my answers provided some comfort and satisfaction but didn’t change anything much.

At first, I tried to become an even better expert – I read even more, studied even harder, and pained my brain to probe the depth of EA even deeper. Gradually (I’m a slow learner), it dawned on me that I may have been chasing the wrong dream. Maybe being an expert would never give me the satisfaction of having a positive impact on the world.

So I decided to become something else instead. Seeing how my ignorance grew with every new thing I learned, I decided to deploy that ignorance as my new strength rather than a fatal weakness I had to overcome. So I declared myself an ‘ex-expert’ (or a double-x-pert, if you will) and started to ask questions instead of giving answers.

It did mean I had to leave the relative comfort of my advisory position. The company couldn’t sell questions; it turned out. Answers were money; questions were not. Hyper-confidence (whether merited or not) was highly valued, humble inquiry was seen as a weakness.

And so I found myself out in the world, eking out an existence as an ignorant seeker, an asker of questions, a learner more than a teacher. Why would anyone pay me for that, I wondered. What’s the economic value of not knowing things?

Well, as it turned out, many people agreed with me. They wanted answers – preferably straight and simple ones, even to the most complex and intractable situations. Even more, they wanted ‘certified’ answers: the tried-and-tested, time-honoured, industry-best-practice answers everyone else had already tried, rather than my suggestion to stop and try something else for a change. Most importantly, they wanted to be told what to think rather than think for themselves. Why else spend any money on me if they still had to do their own thinking?

From time to time, however, I would run into an organisation or individual with a different approach. They would love my ignorant questions, my repeated assertion of non-comprehension, my constant pointing to things that were confusing me. They understood and appreciated that by interacting with my ignorance and constantly being questioned, they were forced to actively explore, analyse, and make sense of their own business, especially those aspects they had always taken for granted. In this way, they would both discover the extent of their own expertise and its limits. And in this process of discovery, they would find more wisdom and practical insights than they could ever get from my expert opinion. Most importantly, because they had discovered wisdom and insight themselves, they were much more inclined to take it to heart and act on it. Who would have thought that their own answers to their own questions could be so much more useful than any of the expert answers available for money?

Helping individuals and organisations make sense of their own business is the most satisfying thing I’ve ever done in my life, especially when it’s really them that are doing the sense-making instead of me.

So, dear Enterprise Architects and Enterprise Designers, if you really want to have an impact on the world, maybe it’s time to question your own wisdom and expertise. Consider the possibility that the best way to get people to see and understand the complexity of their business is not to shower them with models, lists and explanations. Instead, maybe it’s better to use your ignorance as a force that encourages others to construct those models, lists, and descriptions as an expression of what *they* discover and increasingly understand. You can certainly help them create those artefacts, and only by letting them do the exploration will such artefacts become theirs, wholly-owned and understood, ready to be acted upon.

I know it’s a lot to ask of you. Most of you, myself included, have studied long and worked hard to gather everything we know. Most of you are proud of the depth of knowledge and the breadth of our expertise. And so you should be. And maybe, quite possibly, that’s precisely what prevents you from having the profound and lasting impact most EAs tell me they long for.

Maybe, in the words of Thomas Gray, “Where ignorance is bliss, ’tis folly to be wise”.

Editor’s note: At Coaching Enterprise Architects we love to challenge you to think for yourself and support you to learn how to apply the knowledge you have gained over the years. So do reach out to us to schedule sometime with one of our coaches.